- Home

- Tanvir Bush

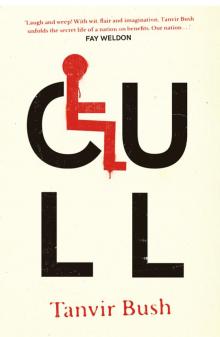

Cull Page 11

Cull Read online

Page 11

How unlucky can a woman be? Dawn has once again been set on just outside the warehouse. Luckily, instead of plastic around her shoulders, she left the house that day wearing an old leather jacket with the collar turned up. So when the kids leap out at her, spraying her with lighter fluid and setting fire to her, it is the jacket that gets most of the grilling. She is able to push herself into the lift where the smoke sets off the fire alarm and … good thinking, Dawn, the sprinklers!

A week later and they can all still smell the charred leather in the lift. Dawn won’t be able to use her left hand for a while but, ‘That’s fine,’ she says. She can’t use it anyway. It’s the dud one. Her eyebrows and eyelashes are gone, and she can’t get the smell of burning hair out of her nostrils, but her face is only a little sore and the tip of an ear is an extravagance she can do without.

‘What is she, fucking Rambo?’ asks Alex. They have closed the offices for the weekend and she, Kitty, Jules and Helen are drinking martinis in the clubroom.

‘Dawn is the toughest woman I have ever known,’ says Jules, spitting out her straw. ‘I should know.’

She should, too. Jules worked for twenty years as a screw in a notorious women’s prison in Manchester. She has seen pretty much all there is to see about people. Alex almost gets up the temerity to ask her how she lost her arms, but is relieved when Helen speaks up. She doesn’t know if she wants to hear.

Helen says, ‘Is it true that the police are refusing to do anything more about the attack? Is that right?’

‘Dawn says the kids were hooded, and although she is pretty sure she knows who they are, she doesn’t think she could identify them. It happened pretty fast.’

Alex sits up. ‘I thought she said they were from the Mandela Estate here on the corner? She said one of the kids called the other one “Danny”. That’s enough to start an investigation, surely?’

‘She said she thinks they did,’ says Jules. ‘But the police say they can’t even begin to go door to door on the estate without more proof. Apparently, the estate is nearly ninety per cent Believe in Better campaigners. I think the cops are scared.’

‘For fuck’s sake,’ says Kitty.

‘That’s awful,’ says Alex. She swigs her martini. It’s delicious. She almost gets the cocktail stick stuck up her nose. ‘Isn’t there anything that can be done?’

‘You could write about it,’ says Helen. She is on her third martini too, but her brown eyes are bright and clear as marbles.

‘They won’t print it at the Cambright Sun.’ Alex bites her lip. ‘They refuse to publish any more crip-attack stories. My editor says it uses up too much of his copy. I tried sneaking in a piece on the suicide rate last week, a follow-up from a story we ran on that poor kid, Laura Shandy, the one who took a dive off the car park. I got an official warning.’

The mention of Laura Shandy causes Helen to spit her drink back into her glass. Alex glances up and is shocked to see Helen has turned a pale greenish colour. Was it the drink? She is about to ask when Jules butts in.

‘Official warning for doing your job? That sucks,’ says Jules and dips her head to get at her cocktail.

Kitty has been thoughtful for a while. Her hand rests briefly on Helen’s shoulder. ‘We just can’t let this happen,’ she says quietly.

‘What’s that, Kit?’ Jules emerges from her martini.

‘Once Only rule?’ asks Helen.

‘Once Only rule,’ says Kitty.

‘What’s the Once Only rule?’ asks Alex.

Jules giggles and then snorts, almost topples and pulls herself back upright. ‘Fuck me once, don’t get to fuck me twice. Let’s just say those kids won’t be setting fire to anyone else any more.’

‘You are joking, right?’ Alex smiles but then peers around the group. Helen’s eyes blaze. Kitty looks at the ceiling. Jules dips back into her drink. Alex’s smile fades.

‘What are you going to do? You sound as if you’re planning … well … violence.’

Jules hiccups. ‘Fire with fire.’

‘No way!’ Alex looks at Helen. ‘Violence doesn’t solve anything!’

‘I disagree.’ says Helen forcefully. ‘Birth is violent. Surgery is violent. Love is violent.’

‘And it might fucking cure those scabrous fucking kids of the need to set fire to anyone,’ says Jules and, standing up, she raises her chin to the ceiling and shouts, ‘Boudicca!’

‘Boudicca!’ echoes Helen.

‘I will not have you spouting that Boudicca rubbish in here,’ snaps Kitty. ‘One sniff of a Boudicca lunatic in our ranks and the next thing you know we will be raided, shut down.’

‘What on earth are you talking about?’ says Alex, but no one tells her.

Tina, the barkeeper, changes the CD on the music system, and the honeyed tones of D’Angelo flow into Alex’s bones. Chris, at her feet, sighs, delighted. Another round of glistening glasses are brought over to the table. There is a slightly uneasy silence. Alex feels she should change the subject.

‘Have you heard of the “Brown Envelope Syndrome”?’ she asks.

‘Eh?’ Jules squints across at Alex, confused. ‘Is it catching?’

Alex tries not to slur but this recent new information has upset her so much she feels impelled to discuss it. ‘It was entered into the International Classification of Diseases three days ago. “Brown Envelope Syndrome; an extreme anxiety created by waiting for, or appearance of, brown envelopes from a welfare agency resulting in depression, hypermania, disassociation and often leading to intensification of existing mental and physical health issues, and on occasion to suicidal thoughts and actions.”’ Alex has the quote by heart.

‘Dear God!’ Kitty drains her glass and signals Tina to mix some more cocktails.

‘I am currently suffering from it,’ says Alex, thinking of a letter next to her computer that she hasn’t yet dared to open. She presumes she has been sanctioned again.

‘So am I and most of the women in here,’ says Helen. ‘In fact, they sanctioned Tilly in accounts last week for not attending her work assessment, even though she was in hospital having dialysis. Her brown envelope stated that they have cut her Basic Benefit, which means she will lose her rent and her husband loses his Caring Support Allowance. Thank goodness for you, Kitty. Without her work here she’d be homeless.’

‘Yeah, right. Thank goodness for me.’ Kitty’s voice is bitter.

Alex looks at her. ‘What is it?’

‘What is it? Jesus, ladies. I can’t single-handedly support the entire British nation of needy crips. I already overemploy, you know, and I get more applications for work every day. We could easily afford to cut at least thirty people from the staff. This is a business, not a bloody charity.’ She drums her fingers angrily on the arm of her chair.

‘We are not entirely helpless,’ says Helen quietly.

‘Yes, you bloody are,’ says Kitty calmly. ‘Singly, on your own, on my own, we are. They are right to crush us one by one. A tick at a time.’

‘Tick tock.’ Helen smiles slightly as D’Angelo kicks in with ‘Brown Sugar’.

‘Tick tock,’ sings Jules. ‘Tick tock till the bomb goes off! Alone we fall, together we appal! Aw, feck. I need a slash.’ She stands up and wobbles slightly. She is in a white T-shirt and Alex, feeling light-headed, thinks she can see the ghostly arms that are not there.

‘You need help?’ asks Helen.

‘Nope. Just hand me my looper please.’ Only it comes out as ‘pooper leese’.

Helen nudges Alex, and Alex feels around for Jules’s device, a long stick with a hook on the end. She is sitting on it. ‘Got it!’ She stands, realising she too has jelly knees, and pops the handle into Jules’s mouth.

‘Ta,’ says Jules, dropping it.

‘Hang on,’ says Alex. ‘I’ll get it.’ She stoops down and promptly falls over.

‘Lightweights.’ Kitty raises her hand. ‘Another round please, Tina!’

‘Darling, I think we might need peanuts,’

says Helen.

Several hours later, after sleeping off some of the alcohol, Alex drags herself out of her bed and staggers over to the computer. Chris chases something in his sleep but doesn’t wake. Alex can’t relax. What was it her friends had been talking about? The Celtic rebel queen Boudicca or … something else? She types and searches, her eyes riddled with retinal light flashes. Past the pages on the Iceni Queen she finds something that raises her heartbeat and eyelids a little. An article from a national newspaper written nearly six months previously.

THE MENTOR

‘Boudicca’: Revolutionary campaigners or just last gaps from the margins? by Gemma Greengrass, Policy Editor

The recent spate of blood-red graffiti appearing on hundreds of government buildings this month is the work of a previously unknown group who call themselves ‘Boudicca’. Little is known about the group’s ethos or intention; they were initially believed to be merely student pranksters or some kind of viral marketing stunt. However, this week a letter was sent to our newspaper with the following statement:

‘We are BOUDICCA.

We are the people that you want to silence. You have condemned us, abused us, threatened us, and now you are hoping we will die out, but we will not.

We are BOUDICCA and we know your game, and we will take action.

By condemning us you condemn yourselves.’

In a reaction to the letter, an H5 police spokesperson denied that the threats should be taken seriously. ‘It is not clear exactly who this group wish to take action against or for. Are they making a stand for immigration, for animal rights, for vegetarians? It is clearly a load of hokum. The police will arrest anyone performing further acts of vandalism, and we intend to track down the letter writer forthwith.’

Alex spends another few minutes searching but finds nothing else and her hangover is threatening to make her vomit. She lurches back to bed and the soothing noise of Chris’s whistling snores.

Alex Takes the

Grassybanks Tour

‘No dogs on the tour.’

‘He is a guide dog. Legally—’

‘Not here. Not “legally” any more, as you well know, Ms … What did you say your name was again? You should have called ahead to make arrangements.’

The nurse is so starched and shiny that light bounces off her like mirrored glass. Alex squints to try to make out the frosty features and can feel that nasty itchy feeling she gets when confronted by people who obviously enjoy the little power they have over others. She swallows, makes an effort, and is pleased to hear her own voice all calm and reasonable.

‘I did call. As you can see, I am on the list as “journalist for Cambright Sun, plus dog”. The woman I spoke to said it was fine. And surely you have many disabled people here as clients with assistance dogs?’

‘Of course not. They do not need their dogs here.’ The nurse’s voice changes pitch slightly. She is now loud enough for the whole room to enjoy the abasement of the blind woman. ‘If you want to make a complaint, you can fill out the form and we will ensure it gets directly to the manager’s desk. However,’ she continues in an aside, sotto voce, to her audience, ‘as it was Mr Skinner the manager who has approved the current state of play as regards … livestock, I don’t think you will get very far.’

Now both Alex’s fists are clenched and Chris’s tail has flatlined. Alex is aware that the legislation around working dogs has been eviscerated. All service-dog owners received letters months ago explaining that new health and safety laws now prohibited them from all restaurants, cafés and public eating areas (to include schools, universities and work-based cafeterias) unless approved by management. This also means that hospitals and nursing homes are no longer obliged to accept assistance dogs.

There is a small crowd of people, mostly children, behind Alex, also waiting for the tour. They are quiet, embarrassed, undecided who to side with or where to sidle to.

‘You can leave the dog outside.’

‘Really?’ asks Alex. ‘Where exactly am I supposed to leave him? In a parking bay? And how then am I to get back in here to do the tour?’

The nurse is as cold as formaldehyde. ‘If you haven’t made the proper preparations, you are wasting everyone’s time.’

‘Oh, I hope you don’t mind me butting in here, but you could come with us!’ A woman taps Alex’s shoulder and she turns to glimpse a serene face, pink cardigan, a rotund apple figure and a mass of cropped dark curls. ‘I couldn’t help overhearing. Gosh, isn’t—’ the pretty black woman pauses to lean in and read the nurse’s name badge ‘—Nurse Dyer having a busy day, children. Maybe we can help her, perhaps even cheer her up a little?’

The nurse makes a shocked, gagging noise and the buzzing contingent of young children in the tour queue politely cover their mouths to giggle. Alex can hear the puffs of sweet laughter and falls deeply in love with her new friend.

‘Now, a quick introduction. I am Jenny Jameson, form teacher for Class Twelve of Bishop’s Middle School.’ She sticks a finger out and taps Nurse Dyer’s clipboard. ‘Right there, Jameson plus fifteen.’

She turns back to Alex. ‘You could come around with us, if that works? My sister is visually impaired, so I kind of know how this works. I would be very happy to loan you my elbow.’

Alex nods, both grateful and moved. It has been a very long time since anyone stood up for her in public. The nurse makes a rather unpleasant sound through her nose.

‘The dog will still not—’

‘Oh yes, this lovely beastie!’ Jenny cuts across the starched-faced nurse, squats down and rubs Chris’s ears. ‘Your dog could wait with Mr Parnell in the school van. He loves dogs. He has about five rescue mutts himself. Priya?’ She turns to a skinny Asian kid with hair braided so tight she is almost unable to shut her eyes. ‘Would you nip out to the van and ask Mr Parnell to come in for a moment?’

And so it goes. Alex finds herself in the middle of a wide-eyed crocodile of nine-year-old children, gripping fast to the warm, soft elbow of Jenny Jameson. They start with juice and biscuits in a large airy room full of brightly coloured sofas and beanbags, boxes of toys and shelves of books, simple cooking facilities and lots of tasteful abstract art hanging from the walls. An enormous mirror set into the far wall scatters sunlight around the room.

‘This is the family visiting room,’ says starched Nurse Dyer. Even she seems a little less rigid in here and hands around a pail of sugar-free sweets with an almost human smile. ‘We just need to go through some housekeeping rules, and then my colleague will show you around.’

There are the usual dreary notes about fire escapes, keeping together, toilets, and then everyone is asked to hand over their mobile phones.

‘I’m sorry?’ This from another journalist, a bald, slender man from the Health Visitors’ Gazette. ‘I can’t let you have it. I use my phone for taking notes and pictures.’

‘Oh, no pictures!’ Nurse Dyer looks furious again. It’ll be a bad old age. Those frown lines are going nowhere, thinks Alex.

‘No, no!’ Dyer wags a finger. ‘Didn’t you read the information on the form? The privacy of our clients is absolutely paramount. If it was thought that we were allowing you to wander through with cameras willy-nilly, I doubt management would allow us to continue with the tour programme.’

‘But then how … ?’ the man begins, but the nurse is frosted glass again. She silently tears off the top pages of her clipboard, folds them into her pocket and hands the clipboard and clean notepaper to the young man. He takes it gingerly.

‘And the pen.’

He takes that too.

‘It is what is called “writing”. I am sure Mrs Jameson can help you out. She is a teacher after all, and such a conscientious citizen.’ She manages to make the ‘citizen’ into a spitball.

Alex squeezes Jenny’s elbow and can feel her twitch with suppressed laughter.

The nurse still has her hand out, and after a mini Mexican standoff the young man hands her his phone. Nurse

Dyer drops it into the pail that had held the sweets, along with the other phones she has confiscated.

‘You can collect them on your way out,’ she says.

‘The kids are behaving really well,’ says Alex. Several of them had wanted to stay behind to play with Chris, so she has promised they can run about the park with him afterwards. ‘A school tour, though? Of a residential home?’ Alex is surprised.

‘Yes.’ Jenny Jameson makes a face and shrugs. ‘It is a new initiative from the educational council and TOSA. All the new TOSA-funded centres have invited local schools to tour as part of their citizenship module. We are even being filmed by our school TV channel, although we’re not allowed to film any patients, of course, only our own children. All footage is to be reviewed before we leave too. That’s all up to her.’ She points to the young woman with the leather jacket and HD camera who is currently shooting one of the children picking his nose.

‘It’s lovely in here,’ says Jenny, looking in a different direction. ‘I don’t know what I was expecting.’

‘Yes,’ Alex has to agree as she sips her orange barley water out of a bright plastic tumbler. ‘I was thinking it would be a little more gothic. I’ve heard that they have recently taken a further hundred and fifty people into the new extension. I mean … well, that’s a hell of a lot of people to care for in one institution. I can’t see how they manage. And all these people are here voluntarily? I don’t get it.’

‘My husband is a paramedic. He was with the NHS but recently took a job with TOSA’s Community Transport Unit …’ Jenny Jameson pauses, bites her lip. ‘Between you and me, he says there’s something a bit odd—’

She is interrupted by the arrival of a lanky man, also in a nurse’s uniform. Alex is sure she recognises him from somewhere but can’t quite put her finger on it. His name is Robin, and he has been working at Grassybanks for nearly a year, he tells the small crowd. He will be their official tour guide. ‘Let’s head over to the sports centre.’

Cull

Cull